The Rise, Fall, and Improbable Comeback of Morris Brown College | BuzzFeed

W.E.B. Du Bois center inside Fountain Hall. Du Bois once taught at Morris Brown College Jarrett Christian for BuzzFeed News

On a late evening this past summer and without warning, one of the oldest buildings in Atlanta caught fire. Gaines Hall — a former dormitory on the campus of Morris Brown College — had been shuttered for years, closed when the school fell on hard times. After firefighters extinguished the two-alarm blaze, what was essentially left of the building was a charred red brick shell. The journey of Gaines Hall from dorm to fire hazard is one that spanned centuries and mirrors that of Morris Brown, the historically black college that owned it for decades.

For many people, the name conjures up the 2006 Outkast song, a tribute to the college that features its renowned band, the Marching Wolverines. But the school holds a special place within the tapestry of HBCUs. While schools like Morehouse, Spelman, and Howard position themselves as go-to institutions for the black elite, Morris Brown cultivated a reputation as an institution that could educate and uplift the most economically and socially disadvantaged black students, only to find itself crippled by a financial scandal. The college had an enrollment of 2,700 students in 2003; today, fewer than 20 are enrolled, taught by mostly volunteer faculty, and the campus is all but abandoned and sold off.

However, Morris Brown is on the rebound. Administrators have overcome a mountain of debt and doubt and have a plan to resurrect the institution. And while Gaines Hall and much of the sprawling campus are gone, the school’s well-maintained quad remains, dotted with small monuments and lush oak trees, bordered by the few buildings Morris Brown still owns and operates. All that’s missing is students.

LaTrey Langston has returned to Morris Brown to celebrate homecoming every year since he graduated in 1999. A member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, he cleans and maintains a decorative fraternity plot on the quad. Langston tends to the grass, sweeps the plot clean, and repaints it with Alpha Phi Alpha’s signature colors, black and old gold. In years past, there would be the usual foot traffic of a college campus. A few days before homecoming this year, Langston completed his ritual in relative seclusion with a burned-out Gaines Hall looming in the background.

“It hurt,” he says of watching news reports of the fire. “When I come back, I can still see myself as a student interacting with my classmates all over this campus and buildings like Gaines Hall. But I think if this space here can remain Morris Brown,” he says, pointing to the green, “then we’ll still have the heart of who we are.”

Black Americans, after being emancipated from slavery, were a people in search of education, of formal schooling they’d been denied during centuries of bondage. Institutions were created to respond to this great demand, colleges and universities founded primarily to train free black people in trades and to themselves become educators. Schools including Virginia Union University, Bowie State University, and Atlanta University sprouted up across the country, many built in former slave states with funding and support from white religious organizations. Today, there are still 107 HBCUsoperating across the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Twenty closed between 1912 and 2013, 13 since 1960. Morris Brown College is distinguished among these schools as one of few actually founded by black Americans.

“To some extent, it suffered from that bottom-up, grassroots approach all throughout its history,” says Samuel Livingston, director of African-American studies at nearby Morehouse College. “Morris Brown was very revolutionary for its time. It was created to be an incubator for that type of thinking.”

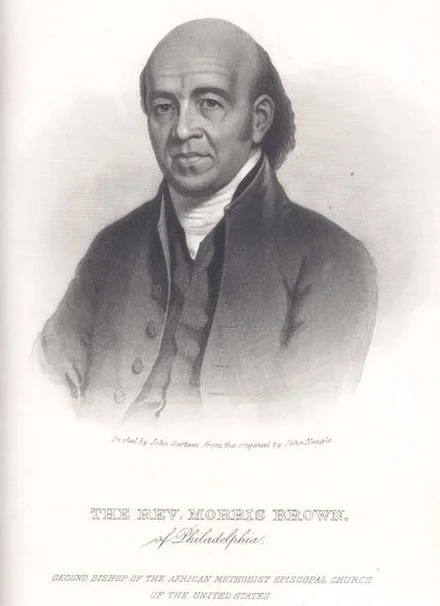

Indeed, Morris Brown College was built on a foundation of black self-determination and resistance to white supremacy. The African Methodist Episcopal Church, which founded Morris Brown, was itself created in 1816 after discrimination within the Methodist church forced black ministers in Pennsylvania to sue for the right to their own congregations. Morris Brown, a free black man, split from his own Methodist church in Charleston a few years later and left to found Emanuel AME Church in the city. In 1822, white authorities learned of the now famous slave uprisingplanned by Denmark Vesey, a prominent black Methodist in Charleston. The plot failed; Vesey and others were executed. Morris Brown and more than 100 other black men were arrested and charged with conspiracy. His church was burned to the ground. Brown was never convicted, but he was held in jail for a year. He emerged in 1822 and would go on to become the second bishop of the AME Church, which today is the oldest independent Protestant denomination founded by black people in the world.

Rev. Morris Brown.

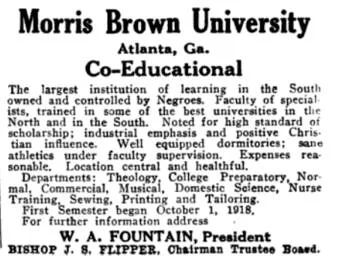

Morris Brown College was established in 1881, 50 years after Brown’s death, and named in his honor. That year, trustees of the AME Church set out to create “an educational institution in Atlanta for the moral, spiritual, and intellectual growth of Negro boys and girls.” The college opened its doors on Oct. 15, 1885 — just 22 years after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation — with 107 students and nine teachers. Unlike Morehouse, Spelman, Clark College, and Atlanta University — all also operating in Atlanta at the time — Morris Brown was a financially independent black institution, funded almost entirely by black Americans through the AME Church. The college got by for decades on contributions from the church’s congregants, and, despite Morris Brown’s resistance to outside funding, it expanded slowly during the first two decades of the 20th century.

The school was originally built on a small tract of land at the intersection of North Boulevard and Houston Street in the Old Fourth Ward, a black residential area in East Atlanta. Within 10 years of graduating its first class, Morris Brown went from one building to a campus with the addition of two structures. The college also expanded its curriculum from that of a primary, secondary, and normal school to include coursework in home economics, nursing, tailoring and dressmaking, printing, commerce, music, and theology.

In the ’20s, however, Morris Brown entered a period of uncertainty. The school was growing too quickly, becoming at one point a university with a seminary and two satellite branches outside of Atlanta. Spread too thin, Morris Brown was forced to undergoinvoluntary bankruptcy but was stronger than ever when it emerged from the financial restructuring. Reverend W. A. Fountain Jr., the school’s seventh president, took office in the fall of 1928 and moved quickly to reorganize operations. The university system was dissolved, the satellite campuses closed, and Fountain successfully pushed donors to increase their contributions to the college.

By 1932, Morris Brown was in good enough financial health to make a move that would position it well for decades to come: When nearby Atlanta University decided to relocate its campus to another tract of land in southwest Atlanta, Fountain persuaded the school’s trustees to allow Morris Brown to lease the university’s former grounds. In doing so, Morris Brown College was placed in closer proximity to Atlanta’s other thriving black schools. It also became the owner of some of the oldest structures in Atlanta: Atlanta University’s Stone Hall, renamed for Fountain, and its North Hall, renamed Gaines Hall.

Fountain continued to develop the college over the next 20-plus years of his presidency before being fired in 1950 amid charges of financial impropriety. During his time, however, Fountain worked to modernize Morris Brown’s curriculum and grow its endowment. The boom was aided in part by Morris Brown’s entrance into an innovative agreement with Atlanta’s other black colleges and universities to create the Atlanta University Center, a consortium that permitted the schools to thrive through shared resources. The thinking was that the individual institutions were stronger and more secure together than they were independently.

For decades, it worked. By 1959, undergraduate Edwina Woodard Hill received the school’s first Rhodes Scholarship, and many Morris Brown alumni would rise to prominence playing instrumental roles in the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, including Bernard Lee, an assistant to Martin Luther King Jr., and Hosea Williams, who led the Atlanta branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Charles Barlow graduated from Morris Brown in 1971 and describes the college as a place where miracles occurred. He grew up on a Georgia farm and spent his early life as a sharecropper. When he graduated from high school, Barlow, now 65, says, he was reading at a 10th-grade level. Regardless, Morris Brown accepted him, and with the help of remedial courses and tough instruction, Barlow graduated and went on to become an executive at Xerox and serve on the college’s board. Days before homecoming this year, he sat in a conference room of the school’s administrative building and reminisced on his time as a student.

“I didn’t know nothing when I came to Morris Brown. I was dumber than a brick, but Morris Brown gave me an opportunity. The people here cared about me and gave me confidence, ” Barlow says. “I love Morris Brown like I love my mother.”

A February 1988 issue of Jet magazine declared that at the time of its 106th anniversary, Morris Brown was enjoying dramatic growth, with enrollment reaching 1,650 students. But by 1992, Morris Brown was experiencing a $6.5 million shortfall and had been placed on probation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), its accrediting body, for poor accounting practices. Then-president Samuel Jolley Jr. worked to turn the school’s finances around, eliminating the debt and generating a surplus of $2 million in 1996. Enrollment reached a record high of 2,111 that year, and donations from corporations, alumni, and the AME Church doubled the school’s endowment to $10 million.

But the landscape was changing for historically black colleges and universities, and the ground was shifting beneath Morris Brown. As was the case for other HBCUs, increased opportunities for black students at predominantly white institutions thinned out the population of prospective students. The rising cost of tuition nationally made what students were left increasingly dependent on federal financial aid. Operating primarily on tuition dollars, Morris Brown was dangerously vulnerable to the whims of the federal government and its policies. Despite surviving so many trials over the years, without a long-term plan for financial survival, the college was on thin ice.

Dolores Cross arrived at Morris Brown in 1998. Cross says she knew running the college — which by then had a reputation for instability — would be hard work, but she was prepared by decades in college administration for the task. She couldn’t have imagined, however, the trials she’d face. Cross lives in Chicago now and gives interviews about Morris Brown rarely and reluctantly. She spoke with BuzzFeed News for this story, detailing her life and time at Morris Brown, in a series of phone interviews.

Cross was no stranger to struggle. She grew up black in the middle of the 20th century and was raised in New Jersey public housing. As a young mother and wife, Cross worked for eight years to complete a B.S. in education from Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey, all the while working part- and full-time jobs as a secretary or typist.

After completing her Ph.D. in 1971, Cross began rising in the ranks of college administration. In 1990, she landed a high-profile job heading up the GE Fund, General Electric’s charitable foundation, which put her in charge of dispensing $30 million in grants annually. For someone who’d worked for decades to level the playing field for vulnerable students, it would have been a meaningful post from which to retire, but Cross was drawn to campus life. After six months at GE, she made a quick transition, becoming the GE Distinguished Professor at CUNY Graduate School before getting the call that Morris Brown was in need of leadership.

Cross assumed the position of president at Morris Brown, becoming the college’s first female president, with a real belief that she could organize the institution and turn it around for good. She’d done it with Chicago State University, a commuter school on Chicago’s South Side that struggled with low retention and graduation rates before she took charge there. Cross entered Morris Brown with that experience in her pocket and the added benefit of access to much-needed potential donors from her time at GE. She told Jetat the time, “I think Morris Brown has an opportunity to become a model of how a historically black college can operate.”

Cross learned before long just how dire the situation at Morris Brown truly was. The school had been through four presidents in 10 years. It was again facing threats to its accreditation, an audit by the U.S. Department of Education yielded recommendations for improvements that had not been satisfied, and a deficit was mounting to the tune of $3.2 million. For the first 20 months of her tenure, Cross says, the school was unable even to pay her salary, which was ultimately funded by a grant she brought with her from GE.

“I came to assume the position of leadership at Morris Brown College not knowing that my journey there, after being a professor, department head, administrator, and a university president was leading me to what would become my crucible,” Cross later wrote in her memoir, Beyond the Wall.

Just two years into her presidency, Cross received a letter from the Department of Education that she says alerted her to questionable, possibly criminal practices within the school’s financial aid and fiscal affairs offices. Former students were lodging complaints to the state and federal government alleging that after leaving Morris Brown they’d been unable to obtain financial aid at other schools because the college still showed them as registered at Morris Brown. A Department of Education review found that Morris Brown was indeed receiving federal aid dollars for 148 students not enrolled at the college. Once again, SACS placed Morris Brown on probation.

Cross says she did all she could to shore up the college’s finances and bookkeeping practices before the situation could deteriorate further. She made decisions that she says were unpopular within the school’s leadership. She fired some senior staff members and brought in auditors from the DOE and other consultants to train the financial aid office and create a system of accountability for the disbursement of student funds. Cross admits to then taking her eye off of the beleaguered offices and relying too heavily on the system of auditors that were in place to alert her to potential mismanagement of student financial aid. In early 2002, it was discovered that a Morris Brown administrator had accessed $8 million in federal financial aid without approval, allegedly under orders from Cross. The money had been used not for student expenses, but to cover the school’s operating expenses and debts.

“Cross came in with a very innovative approach and wanted to empower all students, but the infrastructure wasn’t there,” says Livingston, who was at the time a professor at Morris Brown. “Dr. Cross had very noble intentions, but made some huge financial missteps.”

According to Livingston, members of the faculty took issue with the way communication around the school’s business was being handled. In late 2002, the faculty voted no confidence in the president, forcing the school’s board of trustees to respond. “It put them on notice to look for a new president before things could get any worse,” Livingston says.

Cross and Morris Brown’s financial aid director, Parvesh Singh, quickly resigned amid the public outcry that ensued. Both were indicted for fraud in 2004; Cross was charged with 27 counts. Not wanting to risk years of jail time, she copped a deal and pleaded guilty in 2006 to one count of embezzlement, essentially admitting to misappropriating about $26,000 in student federal aid funding. The other charges were dismissed.

Cross, who emphasizes that she was never convicted of misappropriating funds for any personal use, was sentenced to five years of probation with one year of home confinement and six months of electronic monitoring. In addition, she was ordered to complete 500 hours of community service and to pay a fine of $3,000 and restitution in the amount of $13,942.

Still, the damage to Morris Brown had been done. The college was ordered to repay millions to the federal government, and the Southern Association of College and Schools revoked the college’s accreditation, which meant two things. First, Morris Brown lost membership in the Atlanta University Center, removing any safety net the college could’ve hoped to have from its neighboring HBCUs. And the death blow: Students enrolled at Morris Brown were no longer eligible to receive necessary federal financial aid. More than 90% of Morris Brown’s students relied on student aid, which accounted for more than 70% of the college’s income. Without aid, hundreds of students were forced to leave, many enrolling at nearby schools. Faculty and staff were subsequently laid off.

Livingston believes the decisions made by SACS and the federal government, to essentially starve out the college, were unfair. “It wasn’t a criminal organization; it was a school,” he insists. “[Cross and Singh] could have been punished for the crimes without the judgments that effectively closed the school, but the agenda was not just to correct the school, but to punish us. Professors, staff, students, alumni ended up paying the cost.”

“It’s very sad for me to see,” says Livingston. “Sometimes I bike up to the campus just to see what’s going on, and the state of disrepair is heartrending. We talk now about Morris Brown like a sick elder in the family — ‘How is Morris Brown doing?’ — almost like it’s on a death watch.”

With the assistance of the AME Church and some dedicated alumni, however, the school has been on life support for nearly 15 years. Morris Brown College is open, operating on a meager budget with volunteer faculty and staff and a handful of students who are willing to study at the unaccredited college with the belief that it will one day return to full form. Last year, the college graduated just 21 students.

President Stanley Pritchett stands in front of the now boarded-up Fountain Hall, one of the oldest standing buildings on the Morris Brown Campus. Jarrett Christian for BuzzFeed News

The road to recovery has been fraught. When the dust settled, the school’s debts totaled $32 million. Compounding that were the immediate expenses of maintaining an empty 37-acre campus with 20 buildings. For many years, it appeared as though the school was at a point of no return. Buildings were boarded and news outlets reported one challenge after the other. In 2008, the school was publicly embarrassed when water service on the campus was shut off due to an unpaid bill. The following year, the school lost a building to foreclosure. It was in the midst of this tough, distressing time that Morris Brown officials selected Stanley J. Pritchett Sr. to serve as the 18th president of the college.

Pritchett had never before been the president of a college or university, but he came with decades of experience in public education and, before assuming his position at Morris Brown, he was deputy superintendent of administration and business affairs for Georgia’s DeKalb County Schools. When asked why he took on the daunting task of leading a college that so many had counted out, Pritchett says that he’s always felt connected to Morris Brown’s history, culture, and legacy.

An Atlanta native, Pritchett participated in a “Little Mr. Morris Brown” pageant as a boy and loved to attend other campus events, especially football games and band performances. The school was his late brother’s alma mater, and Pritchett himself received a football scholarship to attend Morris Brown as a teenager. He instead enrolled in Albany State, but his feeling of connection to the college never waned. Pritchett jumped at the opportunity to lead Morris Brown into its next chapter.

“This school is my passion,” Pritchett says. “I wanted to become president in memory of my brother. I knew it wouldn’t be lucrative in terms of compensation, but it wasn’t about that. It’s about making certain at the end of the day that this institution can survive.”

Pritchett, a tall and stoic man with the demeanor of a school principal, approached saving Morris Brown with a focus reminiscent of that of former president W. A. Fountain Jr. in the ’20s. He honed in on the immediate goals of keeping the campus, albeit a scaled-back version, and restructuring the finances to position the college to regain accreditation.

Since 2003, Morris Brown has graduated fewer than 200 students, most of whom are nontraditional students who put their education at Morris Brown and other schools on hold decades ago. Through scholarships and reduced tuition, the college allows them the opportunity to complete their undergraduate education at little to no cost with the hope that their degrees will one day carry the full weight of accreditation.

Tieraney Davis graduated from Morris Brown this past spring. She studied on a full-ride band scholarship, majored in business with a minor in music, and served as president of the student government association. Davis says attending Morris Brown was one of the best decisions she’s ever made. “Other colleges might treat you like a number, but here everyone cares. This is a family,” she says.

Davis’s experience even inspired her mother, Angela Nemard, 47, to return to school, enrolling at Morris Brown. “Words cannot express how proud I was to see her graduate on that day,” says Nemard. “And I decided that I was not going to attend another graduation unless it was my own. I decided to come back to finish.”

Nemard serves as an official ambassador for the college. During the week of homecoming, she and her daughter dress in school gear and engage alumni and visitors on behalf of the college. Davis wears a shirt that reads “Keep calm, I am Morris Brown”; Nemard, a tiara and sash that reads “MBC Ambassador.”

In 2011, Pritchett and the college caught a break when it reached an agreement with the Department of Education to pay back $500,000 of its debt with the remainder forgiven. Then, in 2012, Morris Brown was faced with a decision that could make or break the college. Morris Brown needed to file bankruptcy to address the remaining debt. The school could either file for a liquidation bankruptcy, which would effectively close the school or it could pursue a 363 bankruptcy, which would let the school sell assets, namely property, to satisfy debts. With a steady flow of bills and empty buildings crumbling, school officials made the tough decision to sell a sizable chunk of Morris Brown’s campus to save the school.

With a $7.5 million loan from the AME Church, Morris Brown was able to maintain a small operation through the bankruptcy process, but it still needed a buyer for its property. Meanwhile, the city of Atlanta and a nearby church were entering the market. In a controversial move, the city had recently made a deal to uproot the historic Friendship Baptist Church just east of the campus to build a brand-new stadium for the Atlanta Falcons. The city was looking to further develop the neighborhood near the stadium, and the church wanted to break ground on a new structure. Friendship Baptist and the city’s Invest Atlanta arm together bought property totaling $14.5 million, allowing Morris Brown to satisfy more than $30 million in debt.

The only big hurdle left is for Morris Brown to regain accreditation, something Pritchett hopes it will soon accomplish through scaling down its offerings to focus on in-demand STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), business management, and a small general studies program. Still, the moment was bittersweet — the sale reduced Morris Brown’s land to just seven acres, and three buildings remain in the college’s possession: one classroom building, one administrative building, and its historic Fountain Hall. Included in the structures Morris Brown sold to Invest Atlanta is Gaines Hall.

“It was a tough decision,” says Pritchett, “but at the same you have to look at it from the standpoint that the college is still open. There’s an opportunity for us to get things right as we move forward, and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Homecoming was held at Morris Brown College this year, as it has been for more than a century. There was a day of community cleanup, convocation held at a nearby church, and finally a parade that ended with a cookout on the quad. The event wasn’t on the scale of homecomings past, when the entire area around the campus would pack with cars and the streets bordering campus would fill with tailgaters awaiting the big game and a performance by the Marching Wolverines. Instead, this year, a few hundred people marched from a neighborhood park to the campus.

Without the Marching Wolverines, the college borrowed the bands of nearby high schools to lead the parade. They were met on the quad by a few hundred alumni who packed the yard. There were live performances and food trucks, and, despite lots of bittersweet stories swapped about Gaines Hall, the crowd was in good spirits.

“This week really shows just how special this place is to us,” says LaTrey Langston. “We may not all interact through the year, but we make it a point to come this weekend. Regardless of how this campus looks, there’s always a pilgrimage here on homecoming weekend. There’s no football game, but there’s family.”